At The Height of Jan of Dukla

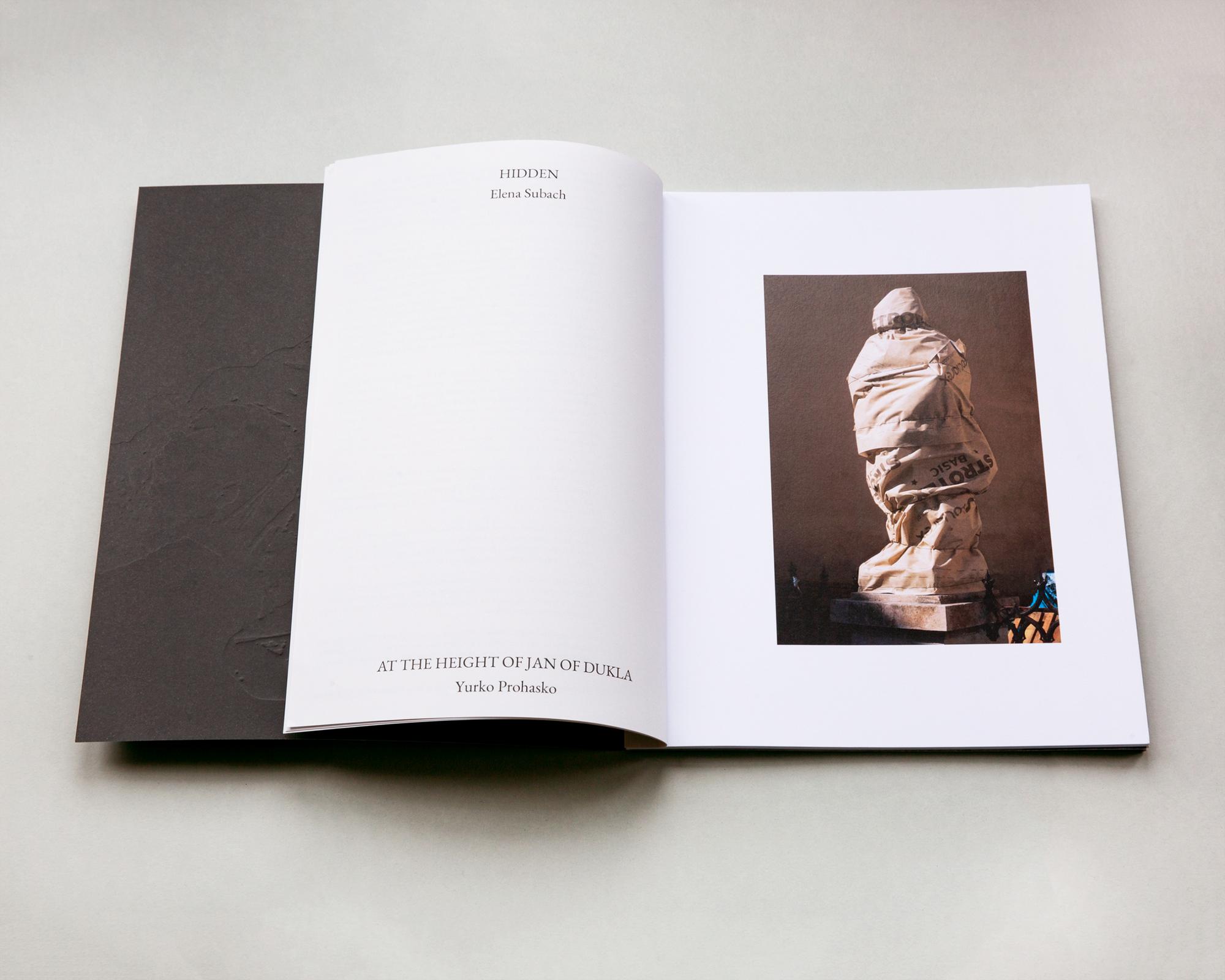

Something I had never, in my entire life, would have thought—that I would find myself eye-to-eye with Jan of Dukla. Alright, 'eye-to-eye' is a a strong exaggeration here, a hyperbole even, and for more than one reason. First of all, in his last years in this world, Jan of Dukla was severely ill and lost his eye-sight. He went completely blind. Second, these eyes, the eyes of a saint into which, under better circumstances, I might have looked in the flesh, were in this instance metal—cast in bronze, unseeing. Even on the bronze statue, it was made obvious that the saint's eyes were the eyes of a blind man. Never in my life could I have imagined that he and I would find ourselves able to look each other in the eye. On the level. It's not that I had ascended to join the saintly host. Rather, it was he who had climbed down—was forced to do so; we dragged him down from his elevation, his exaltation, his height—and yet, apparently, did not disturb the trans-temporal ecstasy he lived.

Up until this moment, the hierarchy was infallible and unimpeachable, and nothing had indicated that this could ever change: there were the angels of the Unseen, the saints in heaven—but also very close to us and our places, somewhere immediately above us—the holy blessed somewhere in the middle, but also invisibly among us, and we, the mortal sinners, below them all on earth. Thus, it had always been my experience to raise my eyes to Jan of Dukla, and I could not have fathomed that one day it might be different.

I liked raising my eyes to him. I liked the whole arrangement very much, if only because it kept things in order. I never felt an urge to challenge the hierarchy, to subvert the ranks, to doubt the disposition. I understood well the holy and hallowed position of the saints, and I knew my own place similarly well. I had never been an icono- or God-clast, not even a rebel, renegade, saboteur or conspirator. I found the fittings all perfectly fit as they were fitted, the order happily ordered the way it was.

With Jan of Dukla I had fallen in love at first sight, when I started coming to Lviv as a little boy. It was the column that first caught my eye: the slim pillar of stone crowned with a carved stone chalice, or perhaps a rococo flame petrified, caught in stone in front of the Bernadine monastery. My beloved aunt, who lived in Lviv, explained to me that the column used to hold up Jan of Dukla, a saint, or at least a holy man. At the very least a holy man. As a consequence of dramatic historical upheavals the poor stone saint had been shot from a tank, deposed from his column, and ground into dust. But here, right here, she said—and showed it to me for the first time—there's another figure of Saint Jan of Dukla, a bronze one that crowns and completes the dome of the monastery's well.

This story of how the saint's one personification was liquidated, of its disqualification, degradation, denigration and erasure prompted in me an even greater affinity for his other figure, the one on top of the well, a feeling of a greater, ennobled solidarity with the one who survived. From that day on, he beaconed me with his metal halo in sunlight and cut a unique silhouette against the sunset. He reflected the copper of fading foliage in the fall and was an inky challenge against the whiteness of the white snow and the white sky in winter. My brother, during his Lviv student days, even wrote a poem about him, with a line about “the white cuffs of snowy shirts”. In this manner, the initial meaning and magnitude of the saint was, for me, visual: too unmistakable was his haloed silhouette, too conspicuous. It became for me one of the most important landmarks and markers of this city.

It was later, however, that I learned the most important thing, namely that Jan of Dukla was a great and powerful protector of Lviv who had rescued the city from certain disaster during the joint Kozak-and-Tatar siege laid to it by the forces of Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Tugay Bey for the two fateful weeks in October of 1648. Lviv's salvation unfolded against the backdrop of a grand virtual pageant, a powerful, grandiose heavenly spectacle, one of those that so richly nourished the Baroque imagination (or were themselves nourished by it).

By the time of this great deed of his—we cannot say here 'life', so let us pause for a definition—his existence in all the manifold dimensions, mystical and mimetic, bodily and backstage, visible and invisible, this- and other-worldly, the (in)corruptible remains of Jan of Dukla (1414-1484) had lain for more than 160 years at rest in the crypt of his beloved Bernadine monastery, where he had moved in search of a more austere law ten years before his death and where he had quietly expired, sightless but prophetic, and was buried and embraced immediately by the affectionate veneration of his brothers and laypeople whom he had served as a confessor and priest and who could not forget the unearthly impression left in them by his station and stature, his word and deed, his confession of sin and profession of faith. It is not known where exactly his holy soul reposed at the epic moment, but it is most likely that it hovered right there above the city and the monastery.

Because on that remarkable day in 1648, Jan of Dukla manifested himself as a great unfurled banner of heaven, a magnificent and terrifying vision in the gloaming October clouds above the Bernadine monastery, in which he then appeared on his knees, with arms raised in ardent prayer. The sight was so awesome and ominous that the siege-layers, full of terror and the fear of God, withdrew from the walls of the all-but doomed city and fled. From wherever distant world he inhabited, from the ranks of angels, Jan of Dukla saved the city where he had spent the last years of his life, the place of his final rest and his final great passion.

This became the beginning of the great and glorious cult of Jan of Dukla, the protector and patron of Lviv, a veneration that extends far beyond the city. In 1733, Pope Clement XII beautified him, and the process of canonization began in 1948, to be completed by Pope John Paul II in 1997.

Everyone in Lviv had always known they were unfailingly under the protection, defense and care of their savior, intercessor and patron. He, in turn, kept his vigil above them, his city and its dwellers. He abides above us, and therefore we have to raise our eyes to him, as we exist below him.

In the last few months, this order has been reversed. We had to take him down from his elevation. Not only did we bring the saint down to our own level, we put him deep underground, in the secret and somber place where he will be safe in the face of this war.

And here I am, face to face with him and marveling at how delicate this mighty defender is, how chiseled and exalted his blind face, how fine his limbs, how tender and vulnerable his whole self in its imperturbable ecstasy.

A defender defended. A protector protected. A savior saved.

Yurko Prohasko

Translated by Nina Murray

15 September 2022